The Hussars are an emblem of Poland and its history. In almost every part of the world, the Winged Hussars evoke associations with Poland in equal measure as Pope John Paul II, Saint Faustyna Kowalska, Chopin or the red and white flag. Several years ago, an idea entitled “Hussars at the Palace” was created. It aimed to ensure that viewers of the television coverage (going out into the wider world) informing on diplomatic visits to Warsaw could see the Hussar guard of honour standing outside the buildings housing the highest State authorities.

One could ask: What does this have in common with Polish and Hungarian relations? Contrary to appearances, quite a lot.

The Hussars are first mentioned at the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries. The defeat in the Bukovina forest on 26 October 1497, in which Poland lost approximately ten thousand people (there is even the Polish saying “All nobles died during the reign of King Olbracht”), prompted the Poles to establish a new type of army. In 1501, the Polish court welcomed the first units of mercenary light cavalry known as the Racs, which were established in the 14th century in Hungary. They were recruited from among Serbs living in Hungarian Dalmatia, Bačka and Banat.

These units experienced their period of growth in the 15th century, when Matthias Corvinus, King of Hungary, Croatia and Bohemia, decided to increase their ranks. After his death in 1490, the Racs were compelled to look for military employment in other locations. Armed with wooden lances, sabres and shields, the Hussars fulfilled a key role in the Polish army.

The word hussar probably comes from the Serbian usar (warrior on horseback, mercenary) or the Hungarian huszár, which is a combination of two Hungarian words husz – twenty and ar – knight's fee or landed estate.

In 1503, the Polish Sejm appointed the first banners (chorągiew) of the National Contingent (autorament narodowy), which were armoured like the Hussars. As the units were required to engage in battles across the extensive area between the Baltic Sea and the Black Sea, the light cavalry gradually became more heavily armoured. This is particularly evident when looking at an engraving taken from the "Prussian Chronicle" by Heinrich von Reden, depicting the arrival of King Sigismund Augustus in Gdańsk in 1552.

The real turning point in the history of the Hussars was the election of the King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, Prince István Báthory of Transylvania, or simply Stephen Báthory. His military reforms transformed the Hussars into heavily armoured cavalry – the most effective military force in Europe at that time.

On 23 June 1576, Báthory issued an official document (sent to the commander of the Hussars, specifying the detailed conditions under which he created the unit), in which he ordered the Hussars to wear Hungarian clothing.

That said, there was already a fashion for Hungarian clothing in Poland at that time. King Sigismund Augustus, and the courtiers following his example, wore vestitus hussaronicus, which can be freely translated as a Hungarian garment consisting of a dolman (dolmány) – a fitted, knee-length jacket made of broadcloth or silk, żupica (a type of short jacket) and trousers.

With time, the dolman was replaced by another item of clothing originating from the Danube region – kontusz (köntös in Hungarian), a type of robe or waistcoat, with characteristic sleeves slit from the armpit to the elbow which, when thrown back, enabled the free movement of the arm when handling a sabre.

During the reign of Stephen Báthory, the Polish language incorporated numerous hungarisms which continue to be in active use. Most of them have military connotations, such as: szereg (row), orszak (procession), giermek (squire), dobosz (drummer), hajduk (highwayman), hejnał (bugle call), and puchar (goblet).

The descriptions of the victorious Hussars’ charges began to feature the word kretes, z kretesem, which comes from the Hungarian tönkretesz – ruin (and entered the common language).

Initially, the Hussars wore close helmets, which were later replaced by zischagges (sisak in Hungarian), a characteristic helmet consisting of a peak with a nasal bar, cheekpieces, a neck guard, and sometimes also wings or feathers

On top of the żupan and cuirass, the Hussars wore a predator’s hide (leopard, tiger or bear hide) or delia (coat/cloak), which was also called czuha in Poland (szűr, cuha in Hungarian). The forearms were protected by vambraces (karwos in Hungarian).

Other elements of weaponry with the Hungarian origin included the horseman’s pick (striking and bladed weapon), koncerz (a type of a long sword) and high riding boots with traditional crescent-shaped iron heels.

However, two other elements were the most characteristic of the Hussars, and later of the entire nobility of the Polish Republic.

The first item is the traditional magierka cap, which was known as Magyar in Hungarian. Made of thick broadcloth, plain woven cloth, it was worn by the Hussars away from the battlefield.

The second characteristic element is the famous Hussar sabre which originates from the Hungarian sabre. Known in Poland already in the Middle Ages, it became widely used with the arrival of the Serbian and Hungarian Racs. The sabres were sometimes embellished with an image of the king or his name, and then referred to as batorówka in Polish (from Báthory).

Magierka caps and Hungarian sabres became inseparable attributes of the Hussars and, following their example, of all Polish nobility. To this day we consider them to be a permanent element of the national dress of the First Polish Republic, on equal footing with żupan and kontusz.

It should be remembered that the King’s orders applied to the entire expanse of the Republic, which at that time covered approximately 1 million square kilometres.

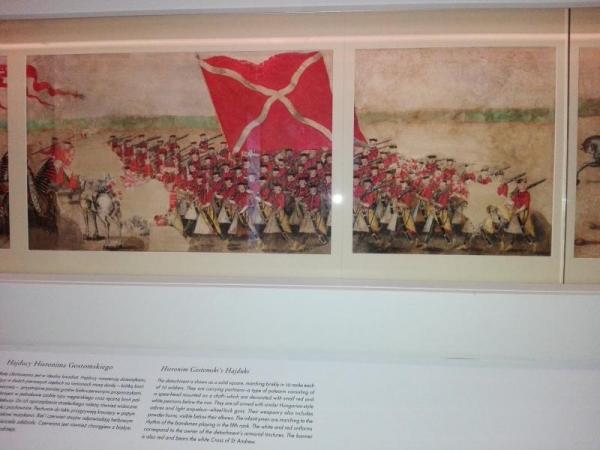

These orders were not limited to the cavalry, but also encompassed the infantry regiments, which King Báthory developed based on......the Hungarian infantry, of course. An infantryman of piechota wybraniecka, an infantry formation established by King Stephen Báthory, was referred to as hajduk (hajdúk in Hungarian – rogue) or wybraniec. His uniform and weapons followed the Hungarian style, i.e. he wore a blue dolman or czuha, the magierka cap, and carried an arquebus, an axe with a long handle and a Hungarian sabre.

During that time, the Hajduks became almost as well-known and respected as the Hussars. Their example was used when creating units which were to guard the rulers and hetmans of the Polish Republic. The Marshal's Guard, which guarded and maintained order at the royal court, was one of many formations based on the Hajduks irregular infantry units.

A wonderful opportunity to discuss these interesting facts anew was the conference entitled “In battle and on parade. Aspects of using the Hussars from the time of the last Jagiellons to the start of the 18th century", which was organised on 15 February this year in the Concert Hall of the Royal Castle in Warsaw.

When opening the conference, the Director of the Royal Castle – Prof. Wojciech Fałkowski, emphasised that this was only the first in many events prepared by the team of the Castle Museum, on the occasion of the current Vasa Year. This event is to mark the 400th anniversary of the construction of the Royal Castle in Warsaw, commissioned by the Polish king Sigismund III Vasa.

The conference featured many fascinating lectures held in the Concert Hall and given by: Tomasz Mleczek, Radosław Sikora, Przemysław Gawron, Konrad Bobiatyński, Piotr Kroll and Zbigniew Hundert, as well as famous historians specialising in Polish military aspects across the ages, namely Prof. Mirosław Nagielski and Wojciech Plewczyński.

One of the guests was Ireneusz Kobrzycki from the Signum Polonicum Association, promoting the traditions of Polish weaponry. He attended the Concert Hall wearing the costume of rotmistrz, who typically commanded between 100 and 180 Hussars. The horse and the Hussar wings were the only things missing. He proudly carried a replica of a sabre from the time of King Stephen Báthory, which was embellished with the King’s image and an inscription.

The second attraction was the opportunity to see the so-called Stockholm Scroll, a 15-metre-long, unique anonymous frieze, which was donated to the Castle in 1974 as a gift from Olof Palme, the then Prime Minister of Sweden. Previously, it formed a part of the museum collection in Stockholm, where it ended up as war booty acquired during the Swedish Deluge.

It depicts the ceremonial entry of the wedding procession of King Sigismund III

and Archduchess Constance of Austria into Kraków on 4 December 1605. Among six hundred members of the procession, we can see a wonderful display of the Hussar cavalrymen and a regiment of Hajduks, the Hungarian infantry soldiers.

This priceless historical source enables us to learn about clothing, uniforms, armament and equipment, as well as the customs of the period. The scroll is accompanied by an exhibition of items on loan from the Polish Army Museum, which include rapiers, halberds, muskets and a Hussars zischagge.

The exhibition runs until 10 March 2019.

Salomon Rysiński, of the Ostoja coat of arms, in his work from 1618 entitled Proverbiorum polonicorum quotes the following Polish saying from the start of the 17th century:

“A Turkish horse, a peasant from Masuria, a magierka cap, a Hungarian sabre.”

(An Arab horse, a peasant from Mazovia, etc.)

Artur Kolęda