Fronda Publishing House presented Polish readers with the figure of Erzsébet Galgóczy, a contemporary Hungarian mystic and stigmatist, little known in our country. We discover her life story and reflections, based on and from very reliable sources, i.e. confirmed notes of Erzsébet herself and written testimonies of people who knew her. The book is accompanied by a great foreword by Fr Robert Skrzypczak, who introduces the reader to an extremely difficult, even for believers, subject of suffering, which was the vocation and essence of the life of this Hungarian mystic.

Erzsébet Galgóczy lived between 1905 and 1962. She felt the need for martyrdom even as a very young child and she was seriously ill on many occasions. She had an extraordinary love for Jesus and a growing interest in the matters of faith. When she turned 15, the illness that had immobilized her for the rest of her life shattered her childhood dreams of becoming a teacher, nun and missionary. It turned out that God had planned a different path for her, which she had entered not without fear and resistance.

Suffering without making sense of it is destructive in every dimension - carnal, mental and spiritual. Reading notes of the Hungarian mystic, an interview with Jasiek Mela came to my mind which I conducted a few years ago. He told me about his experiences and thoughts when, at the age of 13, he was lying in hospital after an electric shock and amputation of his arm and leg: "If we want it, [suffering] ennobles, if we don't want it, it goes to the dumpster. (...) Fr. Łada visited me, (...) and said that suffering can be a kind of prayer that can be offered for someone. I was immediately struck by a thought: I'm offering this for Peter. It gave meaning to any amount of suffering. I thought that even if I don't get out of this hospital, it all goes to my brother's account as it were. There's nothing worse than a sense of meaninglessness, and those words helped me find that sense."[1] The meaning of Erzsébet Galgócza's life was to do God's will, and God invited her to suffer for given, threatened with condemnation, human souls and her beloved homeland - Hungary.

Reading Erzsébet's notes we accompany her on a journey that is unimaginable, very difficult to understand and acceptable to most people. The subsequent stigmatist goes from rebellion against pain and anguish and a dream of recovery supported by many prayers to understanding the value of suffering, accepting it and offering it as compensation. The Hungarian female is suffering both physically and spiritually. Her beloved Jesus, gradually strips her down from everything, and she gives everything back to him. "I wanted to help everyone. I wanted to take on all the anguish. There was no such torment which, if I had been told about it, I wouldn't have taken it upon myself, to make Jesus happy, to give him at least a little joy. That's why my ailments were multiplying, because it seemed that Jesus was accepting my sacrifices." - she wrote in 1934. Besides pain, her life's path is filled with extraordinary graces and mystical experiences. Erzsébet has a deep, direct relationship with Our Lady, whom she calls Marysieńka at Her request. Mary is her spiritual guide, teacher and comforter. When there is no one to care for her, a nurse is sent from Heaven – Saint Catherine of Siena. Young Erzsébet never heard about her before. Someone not from this world also helps her with cooking and other work, as eyewitnesses tell us.

Erzsébet's sufferings intensify during World War II when she offers them for her war-ravaged country, the dead and dying. She lies in the basement, in pain, with a fever and an infection that had poisoned the wounds covering her body. Deprived of daylight for many days, she listens to the swish of artillery shells, the bang of bombs. People hiding with her inform her about the dramas taking place on the streets of the city. Sometimes she herself is a direct witness to them, when Our Lady takes Erzsébet with her in an incomprehensible way on a journey through ruined Hungary, whilst she is still physically on a bundle of straw in a corner of the basement. There is a moving story of a young soldier who died in the courtyard of the house where she lived. His body was dumped on a street, where it lay unburied for five days. A letter found on deceased made it clear that his old parents were waiting for him at home. Erzsébet, full of compassion for the deceased and his loved ones, offers her sufferings for his soul, so that he can go to heaven. "He had no coffin, no one anointed him, no blessing, but my spirit found his grave many times a day and I prayed for him. Jesus, I need you to have mercy on him! Take him in, I'm willing to face Purgatory's sufferings for him, but have pity on him!" When people, hiding with her in the basement, whisper that it would be better for her to die, because her suffering is so great, she prays ready give herself "until the last drop of blood". "I want to do my share in the work of redemption." - she writes in 1944.

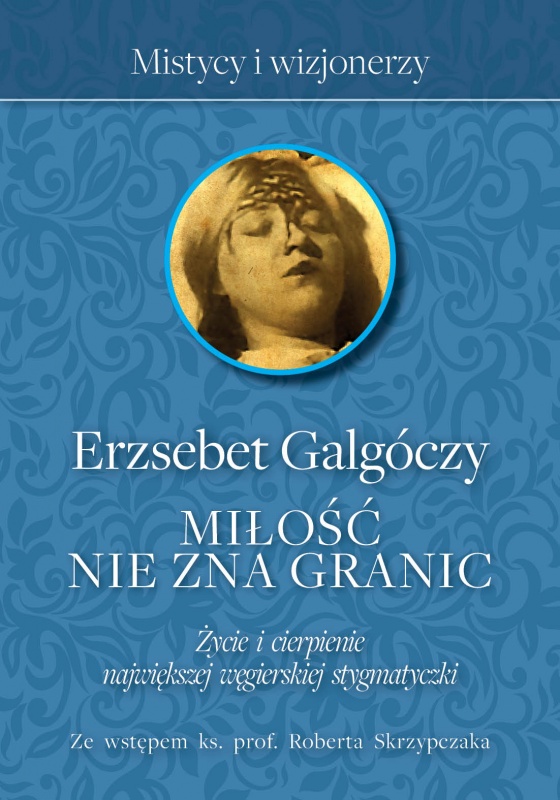

Those who knew Erzsébet Galgóczy talk about her strength, serenity, warmth, understanding of other people's problems, how nice and edifying it was to be in her company and... how well she cooked on the small stove next to her bed! They say that she didn't complain or grumble. The few pictures available on the Internet show a woman with a bright, maybe pale face – sometimes smiling, and sometimes tired and with dark shadows under her eyes. In others you can see her in ecstasy, with her forehead deeply wounded by a thorny crown. In the words of the author of the introduction to the Polish edition of the book Love knows no boundaries: "This book will shock some and fascinate others. In any case, nobody will be indifferent to it" and I fully agree with his words. It is worth taking the time to read this extraordinary biography, especially since the language is catchy, inspiring and perfectly translated.

Erzsébet Galgóczy, Love knows no boundaries. The life and suffering of the greatest Hungarian stigmatist. Fronda, Warsaw 2020

Marta Dzbeńska-Karpińska

[1] https://www.takrodzinie.pl/artykul/zrobilem-szalik-na-drutach, access on 23.06.2020